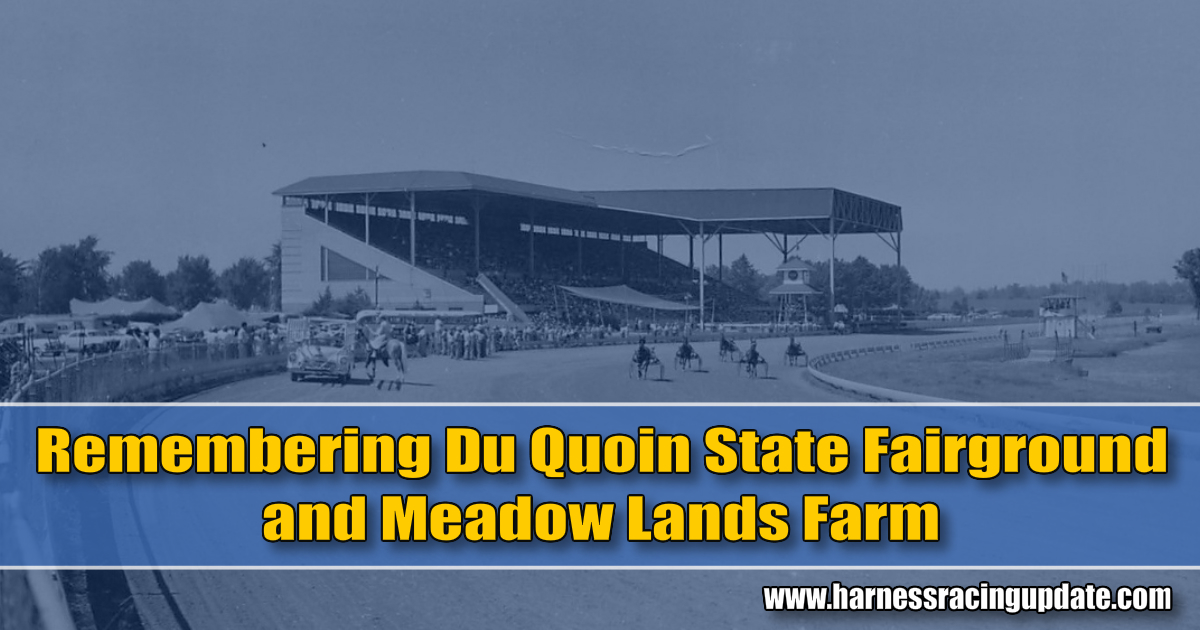

Remembering Du Quoin State Fairgrounds and Meadow Lands Farm

by Dean A. Hoffman

If there is a more beautiful setting for harness racing, I’ve never seen it.

The mile track at the Du Quoin State Fairgrounds in southern Illinois provides a beautiful pastoral panorama that makes it so delightful for spectators. They could sweep their eyes across the scene and focus on the racing competition without many of the unsightly distractions found at other tracks.

It was this natural beauty that spectators and horsemen enjoyed when attending the races at Du Quoin. Harness racing had its roots in rural America and no setting better allowed horses to display their talents on a more glorious stage.

That is why the Hambletonian enjoyed more than three decades of glory at Du Quoin, starting in 1957 and continuing through 1980.

No doubt about it, however: Du Quoin was remote. It was in the “Little Egypt” section of southern Illinois. It was over 300 miles south of Chicago, and 90 miles southeast of St. Louis. Getting there was challenging by air or by car. The nearest airport of consequence was in Carbondale, the home of Southern Illinois University, 20 miles to the south. That made it challenging for the national media to cover trotting’s greatest event in the pre-Internet era.

Racing continues today in Du Quoin but gone are the glory days of the Grand Circuit, the week around Labor Day when the best horses and best horsemen would trek to Little Egypt for the chance to race on a track usually groomed to billiard-table perfection.

Harness racing hospitality in Du Quoin was brought to its pinnacle by brothers Don and Gene Hayes, who owned a Coca-Cola bottling plant and who cherished an abiding love for harness horses. In 1950, they scored a remarkable double when their colts Lusty Song and Dudley Hanover, selected and developed by Dr. H.M. Parshall and driven to victory by young Delvin Miller, won the Hambletonian and Little Brown Jug.

The only thing better than winning the Hambletonian, the Hayes brothers agreed, would be playing host to the Hambletonian. They gained that privilege in 1957 when Good Time Park in Goshen, NY, closed. So the best 3-year-old trotters would now fight for the biggest prize on a mile track a thousand miles west of Goshen.

The Hayes brothers weren’t content to merely play host to the Hambletonian; they also were determined to showcase it and provide the participants with unparalleled hospitality. Owners and horsemen were treated royally and the pre-Hambletonian parties on the lawn of the Hayes homes at the fairgrounds were legendary.

The first Hambletonian in1957 came down to a duel between a colt and a filly with the same initials in their names: Hickory Smoke and Hoot Song. With 22 entrants, the race was split into divisions and both horses won two heats. Hickory Smoke edged the filly in a third-heat raceoff.

It seemed that every Hambletonian provided new drama and dramatic demonstrations of ever-increasing trotting speed. The fastest mile ever in the Hambletonian at Good Time Park in Goshen had been Hoot Mon’s 2:00 in 1947, but that mark took a terrible beating at Du Quoin.

The filly Emily’s Pride lowered it, first but by 1964 the Hambletonian time standard was at 1:56.4, courtesy of the speedball Ayres.

The Hambletonian, of course, was part of a larger Grand Circuit week that provided a showcase for other stars.

Despite the unrelenting efforts of the Hayes family, there were persistent attempts to move the Hambletonian to a more accessible and modern setting and rid the race of its image as the Corn Tassel Derby. Many tracks made valiant efforts to secure the prize.

Those efforts all failed until a Super Track called the Meadowlands opened within the shadows of Manhattan skyscrapers. Track officials at the Big M dreamed big and they set their eyes on the prize, ultimately playing host to the first Hambletonian on a rainy afternoon in August, 1981.

Illinois racing officials had a ready replacement in a new event called the World Trotting Derby, which gained enormous prestige and attracted the best sophomore trotters until its demise in 2009.

Racing continues at Du Quoin but the glory days of the Hambletonian and Grand Circuit are now a fading memory. Harness racing in Illinois suffered several grievous blows that vitiated its once-vital racing program.

Meadow Lands Farm, Meadow Lands, PA

After serving his country on the CBI (China- Burma-India) Theater in World War II, a young Pennsylvanian named Delvin Miller returned to his roots in hills of western Pennsylvania determined to make a mark in harness racing.

To those who were watching closely, Miller had already made his mark. He won the 1940 Fox Stake, then by far the greatest prize for juvenile pacers, with a calf-kneed colt named Blackhawk. Even during the dreary years of the Depression in the 1930s, young Miller impressed others with his ability and ambition.

But he wanted a farm of his own and ultimately a stallion. In both cases, he chose wisely.

Miller bought a farm on hilly ground 25 miles south of Pittsburgh in the hamlet of Meadow Lands, not far from Route 19 that ran south out of Pittsburgh. It was surely no rival to the showplaces of the Bluegrass in Kentucky, but Miller was a practical horseman first and foremost. The farm was christened with the name of the town: Meadow Lands.

After he had the farm, Miller needed a stallion. Like real estate, stallions were not cheap. And Delvin Miller was not rich. He surveyed the standardbred scene and found such stars as The Widower and other top flight pacers suitable for stud duty.

For advice, he learned on his mentor, Dr H. M, Parshall, a veterinarian who spent his career training and racing horses. Fifteen years separated them in age, but Miller assiduously soaked up the wisdom of the Parshall.

“You don’t want just any horse,” emphasized Parshall. “You want Adios. I guarantee you he’ll sire good fillies.”

“No one could sell me quite like Doc could because I believed in him so much,” Miller said later.

Adios sold at auction at the Tattersalls facility in Kentucky and Miller was short on cash for a man long on ambition. When the bidding reached $20,000, Miller was out of money but raised one finder to indicate a bid of $20,100. Auctioneer George Swinebroad took it as a bid of $21,000 and hammered the horse down to Miller.

Miller protested because 900 bucks was, after all, a lot of money to him. But sale officials were resolute.

So Miller trucked Adios back to western Pennsylvania and began hustling mares for his new horse at $300 for a live foal.

Miracles soon began to happen. The sons and daughters of Adios represented a new dimension in standardbred speed. The first 2:00 juvenile pacers of both sexes, the colt Adios Boy and the filly Adios Betty, set their marks in 1953.

In 1955, Adios was syndicated for $500,000 with Hanover Shoe Farms and Max Hempt sharing ownership with Miller. Adios remained at Meadow Lands until his death a decade later.

Miller added other stallions, but they all stood in the shadow of Adios. That included Dale Frost, although in 1960 his son Meadow Skipper was foaled and the dark brown colt became the heir apparent to Adios in pacing domination.

While his stallions stood at Meadow Lands Farm, Miller raised his yearlings at his boyhood home near Avella, PA. It was rugged, hilly land.

The late Norman Woolworth visited the farm in Avella and marveled at its terrain.

“I’m surprised that the yearlings didn’t have one leg much shorter than on the other side because they were raised on such steep hills,” he joked.

When the Adios Stake was started in 1967 at The Meadows, Miller and his wife Mary Lib played host to epic parties to welcome the Grand Circuit crowd.

Meadow Lands Farm exists today primarily as a training center for horses racing at The Meadows, but visitors to the farm can make a pilgrimage to the gravesites of both Adios and Dale Frost.