Horses have given Ellen Harvey everything and she won’t betray their trust, Part 1

by Murray Brown

Most people would agree that Ellen Harvey has led a most interesting life. So much so, we’re going to split this column into two parts. Just as an example, how many people in the sport can you name living today who have had a close relationship with two of the equine giants of the sport’s history, the great stallion and racehorse Adios and then a few years later, another great stallion and racehorse Albatross? The list is a pretty short one. It consists of Ellen and her siblings: her brother Leo and sisters Anne and Kathryn.

I suppose it begins with Adios. Let’s start there.

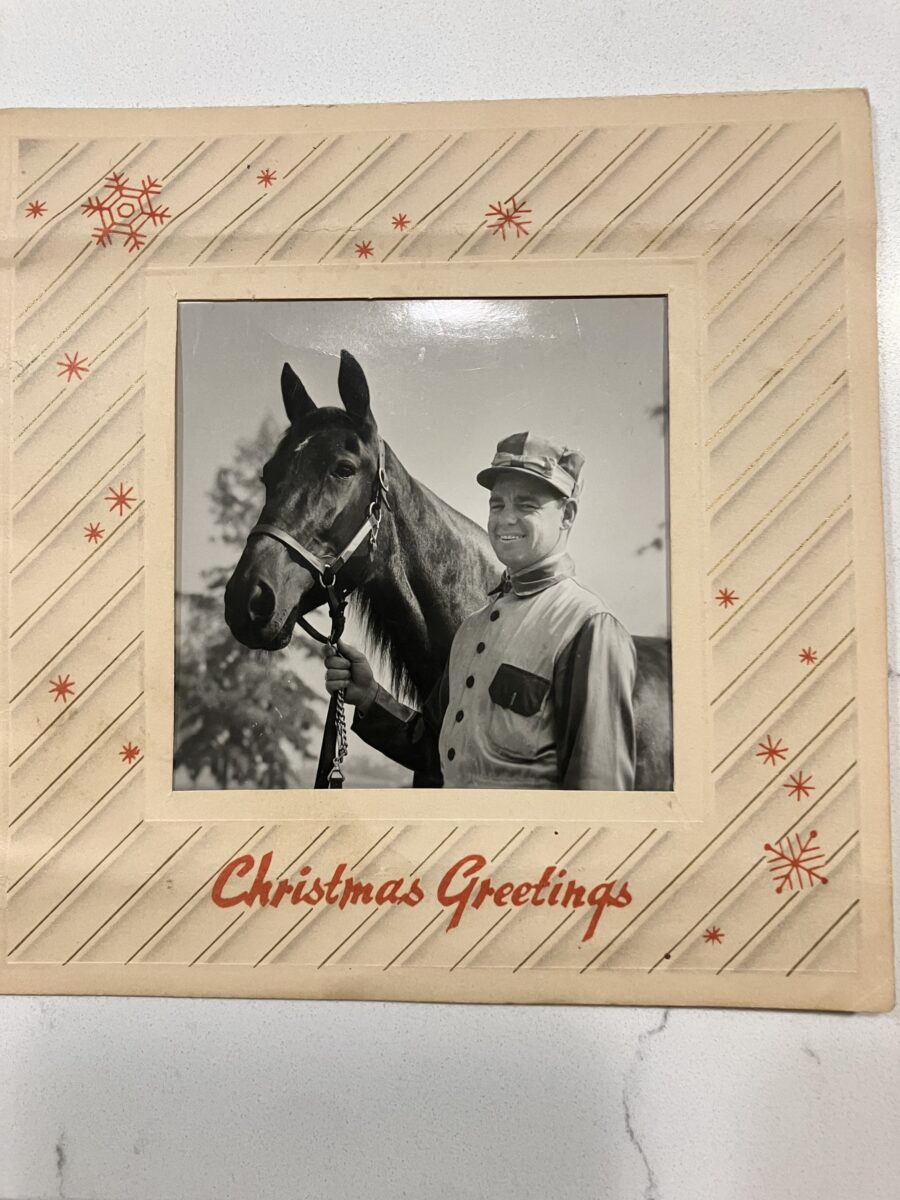

“Actually, it begins a little before that. My dad [Hall of Famer Harry Harvey] was a second trainer for Delvin Miller. Delvin had three horses in the 1953 Hambletonian; dad had driven Helicopter all along and he drove her that day.

“She made a break before the start in the first heat. She then scored from post 17 in the third tier of the second heat and won to force the third heat. I recall dad saying that in deep stretch, he was alongside Tom Berry driving Kimberly Kid, the favorite. Tom had given him his first job in the business, as a groom, in 1947. Kimberly Kid was fading, losing his crupper, something dad said he’d never seen before or since. Helicopter went on by and won, but the irony of beating the person who was the reason you were there was not lost on him.

“My mother, Cornelia, was raised near Goshen; she was home from college the summer of 1953 and riding saddlebreds stabled at the same farm as Delvin’s horses. Turns out that winning the Hambletonian is a really good way to impress a local girl; they married a year later, after my mother graduated from college.

“My dad grew up on a farm in Vermont and my parents wanted to raise children in one place. Adios was in his ascendency then and dad left the racetrack to manage Meadow Lands Farm for Delvin.

“All my young life was spent on Meadow Lands Farm. We lived on a satellite farm and the yearlings were raised at Delvin’s ancestral family farm, Bancroft, about 25 miles away. Dad was there weekly and often said that Bancroft was a major element in the success of Adios’ progeny. ‘A lot of those horses outraced their pedigrees,’ he said.

“I’m hard pressed to fully describe just how hilly it was. The yearlings were up and down hills, and if I recall correctly, water was at the bottom of the hill and feed at the top. That area was rich with bituminous coal and I suppose the water and grass were replete with minerals that contributed to bone density.

“By the time I was old enough to understand the effect Adios was having on the sport, he had already done so. There was nothing too extravagant for Adios. He had a double stall with windows all around and straw up to his knees. His stall was air conditioned at a time when very few people had air conditioning. I’m not sure Delvin and Mary Lib had it. He had a radio tuned in to his favorite station. You couldn’t change the station or Adios snorted and stomped. Every year Delvin and Mary Lib had a birthday party for him and always, there was media and a cake concocted out of oats and carrots.

“The walls outside his stall were filled with pictures of Adios with celebrities. I recall Eddie Arcaro coming to the farm — in a suit — to meet Adios.

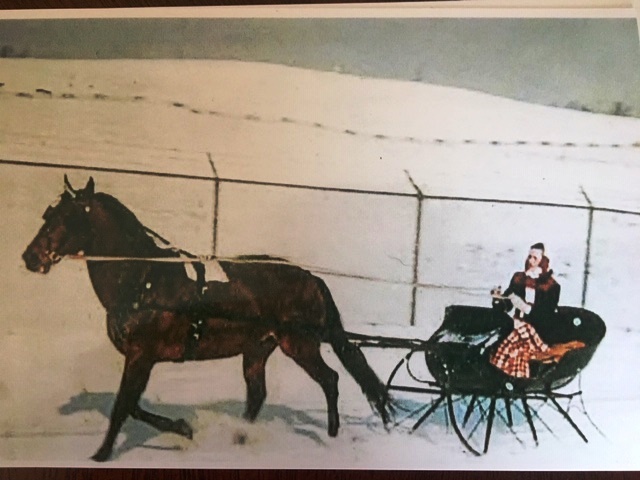

“My mom occasionally rode the stallions, but never Adios. She knew how valuable he was and didn’t want to take chances. Delvin had all manner of horse drawn vehicles, including a surrey that really did have a fringe on top, and a one-horse sleigh. One Christmas, mom was convinced to drive Adios in the sleigh along the berm of the street along the farm.

“It was a great time and place to be a kid. We had ponies and a pond. Dad cut trails in the woods for us to ride and hike. Buster Henry, Adios’ groom, lived in an apartment over Mary Lib and Delvin’s and he and his wife Lucy babysat me. Buster taught me how to dunk a donut in (very weak) coffee and I ate Cocoa Puffs in front of their TV, forbidden pleasures at home.

“I knew Amy, Delvin’s mother. She lived at Bancroft after Delvin’s dad died in the 1918 flu epidemic; she was born in a sod house in South Dakota. She made homemade bread and apple butter for me and had a Lincoln Log set I played with.

“We had Christmas twice a year. Delvin and Mary Lib went to Florida right after Thanksgiving. Mary Lib cooked Thanksgiving dinner and gave us Christmas gifts.

“After Mr. Sheppard bought Adios in 1960 for the then unheard-of price of $500,000, Adios developed laminitis. There was a steady stream of vets to try to manage this, but in June of 1965, he was euthanized. It was a terribly sad time. Dad had devoted so much time and care to looking after this great horse.

“Without Adios, Delvin started downsizing. Dad saw the handwriting on the wall. He bought the farm we lived on, plus the 100-acre farm next door and started a small breeding operation with two stallions. In his spare time — I’m joking, he had no spare time — he also returned to training and driving at Arden Downs. He raised yearlings, trimmed their feet himself and terraced about 20 acres of the farm to prevent erosion. Maybe there was someone who could outwork dad, but I doubt it.

“Around that time, Jim Harrison was editing the original Care and Training of the Trotter and Pacer and dad wrote the farm management chapter. We still have a photo Ed Keys took of a kitten when he was at our farm to take photos for the book.”

Author’s note: It is my belief that Adios’ progeny most certainly outraced their pedigrees; perhaps to some degree because they were raised at Bancroft, but more because of the absolute dominance of Adios in the breeding arena. There were numerous other offspring of Adios that were raised elsewhere that also outraced their pedigrees.

Thus began the Albatross era?

“At first, dad raced mostly at The Meadows and the Pennsylvania fair tracks. I remember going with him to Gratz. There were maybe five races, each race went two heats. He won every race on the card.

“The stable grew to the point where he was in two barns and had two second trainers. The home builder Ed Ryan and 84 Lumber’s Joe Hardy gave him horses to train, as did Art Rooney and his son Tim, and Saul Finkelstein on the recommendation of Jimmy Cruise.

“Then came Bert James. Mr. James was a former Canadian automobile dealer who became involved in all facets of the game, especially in racing. He had consigned a peanut-sized Meadow Skipper colt to the 1969 Harrisburg Sale. The colt didn’t bring very much, so James bought him back. That colt was Albatross.

“I don’t recall seeing Albatross train but I heard a lot about his kicking. He kicked like crazy in his stall. Dad tried various stalls/windows/neighbors to find a place he liked. My brother was a wrestler and through his coach, dad got wrestling mats to put up in his stall; he kicked those, too. I suppose he just had so much pent-up energy.

“Dad built a paddock for him in the centerfield at Arden Downs and he had a portable version that shipped with him when he raced.

“I don’t know as I ever saw Albatross race other than his first baby race at The Meadows. He won easily in about 2:07 and people were stunned. I was in middle school and almost none of his races were anyplace we could get to easily and my mom had her hands full with four children and bookkeeping for the farm and track.

“Albatross kept racing and winning. Dad brought home fancy blankets most weeks and newspaper stories from wherever he’d raced. One of his few losing efforts at 2 was before hometown fans at The Meadows where he was defeated by Billy Haughton’s Seton Hanover; I guess I was there but I’ve scoured that from my brain.

“Dad’s goal above all others with Albatross was to win the Fox Stake, then, without doubt, the premier event for 2-year-old pacers. I cannot remember him being more happy, ever, winning a race than that one. My siblings and I taped paper together and made a sign (“Congratulations Albatross”) that we put up on the fence along where he parked his truck when he got home, yet again, in the middle of the night.

“I recall dad saying many times, to various people interviewing him, that it wasn’t so much his speed or brain or his conformation, that made Albatross great, it was his ability to convert oxygen to energy.

“I was 13 when all this was going on. I never worked at the racing stable or the farm, there was no watching races on satellite then. I heard one end of phone calls and read the stories in the newspapers dad brought home.

“There was a break in his schedule. He had a big race coming up the next week. He tried to get him a race, but all he could find was one against older horses at Roosevelt. I remember some grumbling about it. That was all that was available, so he took it.

“Albatross got pretty much every kind of award he could get that winter. Dad called Frank Ervin and asked him what he did with Bret between 2 and 3 – did he let him down, jog him all winter? Frank advised to ‘do a little something’ with him every day and not send him away and that’s what he did.”

Author’s note No. 2: I believe that through almost 70 years in the sport I’ve never seen a more dominant 2-year-old than Albatross. He did things among which was something that had never been previously done and almost certainly will never be replicated. He took on and defeated older Saturday Night Specials at Roosevelt after being given the outside post position.

Next week: The devastating loss of Albatross