Only a dope would think harness racing doesn’t need serious change

Nearly four years after the horse doping indictments — and nearly three decades after I started covering the sport — shockingly little has changed to improve harness racing.

by Dave Briggs

Close to 30 years after I started covering harness racing, I don’t love it any less. But I am growing tired — tired of seeing something I love continue to decline due, mostly, to those in charge refusing to embrace much-needed change.

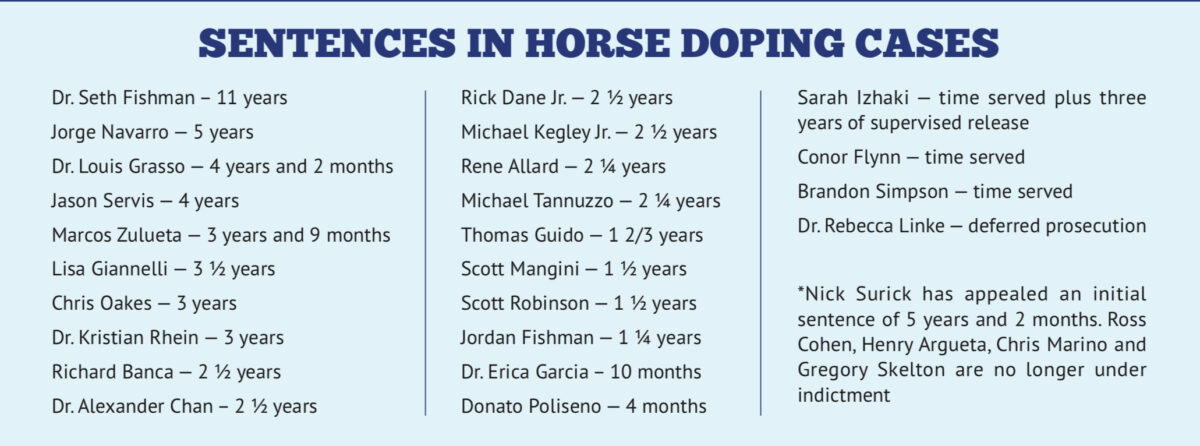

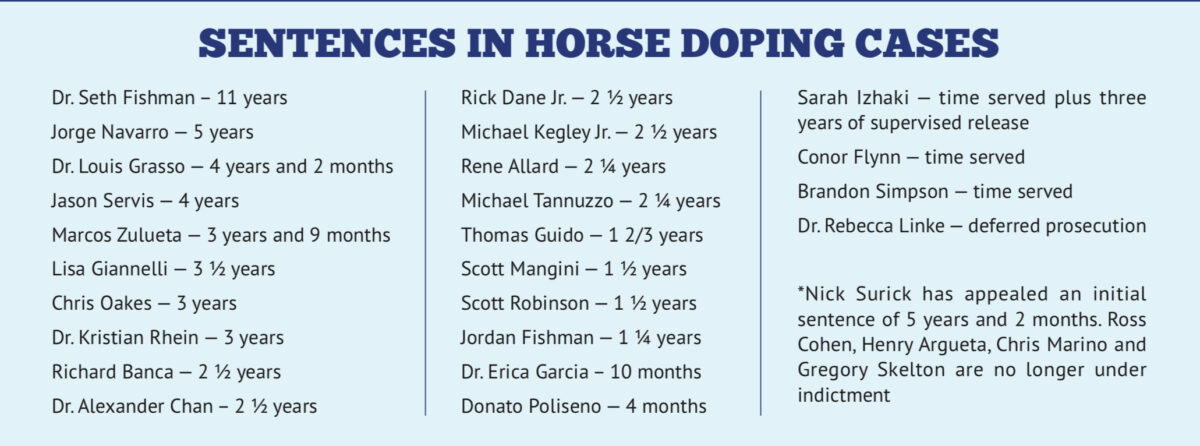

I’m not sure if the lack of movement is incompetence or laziness or lack of foresight or some wild belief things are just fine — perhaps all of the above. But if watching some 20 people go to jail for a collective total of nearly 60 years at last count (see box) for horse doping wasn’t the wake-up call the sport needed to undergo wholesale change, I’m not sure anything will do the trick.

It will be four years ago in March that the FBI and the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York announced the first indictments for what is straight-up cheating and horse abuse. The outrage was short-lived and has long since dissipated.

Since that time, little to nothing has changed to address the scourge of performance-enhancing drugs in a sport clearly in the cross-hairs of animal rights forces that haven’t the slightest interest in appreciating the subtle differences between standardbred and thoroughbred racing. On that score, harness racing is just lucky few people know this particular brand of horse racing exists.

Worse, harness racing has done little to advance what should be its number one rule: Protect the welfare of the horses at all costs.

Even after one of the worst scandals imaginable — where the FBI had to be called in to nab people so unscrupulous they harmed horses they purported to love for personal gain — harness racing still can’t even agree about what constitutes an effective drug testing program from state to state let alone figure out how to properly police itself.

God forbid an epic scandal involving animal welfare brings action and reason to the system.

First, the emphasis and funding must shift more to the only proven method of catching cheaters — surveillance. Second, despite the relative ineffectiveness of drug testing, regulators need to also sharply increase fines for the most performance-enhancing of the drugs — the ones that are Class 1 or 2 that should almost never be in a horse for any reason.

At the same time, regulators need to stop handing out fines and suspensions for positives triggered by nanogram levels of therapeutic medications designed to keep horses healthy, not cheat. At one billionth of a gram, how could an antihistamine possibly give a horse an advantage over others? Why should a trainer be punished for trying to help a horse breathe?

There’s also the significant issue of contamination that needs sound reasoning from regulators who should know by now that a rash of positives for the same drug from the same paddock wasn’t a group of trainers getting together to try to cheat.

But then, logic is not a quality often held by regulators who are, all too frequently, bureaucrats more focused on making few waves and keeping their sweet government gig than doing their jobs to protect horses and the betting public.

Little wonder John Campbell has, sadly, only made limited progress in his quest to bring much-needed universal rules to the sport despite a huge effort. I feel deeply for him. If he can’t get it done, I can’t think of anyone that can.

In March, it will be seven years since Campbell became president and CEO of the Hambletonian Society and began trying to bring reason to the madness. But since harness racing is largely a series of warlords and fiefdoms, there just isn’t a compelling reason for, say, the Pennsylvania regulators to get on the same page with the ones in New York or New Jersey or Ohio or anywhere else. They will just worry about their own states, thank you very much. The betterment of the sport be damned.

That was one of the promising parts about the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA) at least on paper — it was a step toward horse racing governing itself nationwide.

Yet, instead of working from the inside to soften the most egregious parts of HISA, what does harness racing do? Its own governing body tries to bring HISA down. You can’t make this up.

What does the public see? That harness racing isn’t interested in integrity or the safety of its horses and participants. That’s not true, of course, but try explaining that to someone that doesn’t know a standardbred from a salamander.

And public perception does matter, especially for a sport that desperately needs some public to like it for it to have a future.

Speaking of warlords and fiefdoms, the racetracks don’t do the sport any favors either by protecting their own turf at the expense of others. I guess, like the regulators, one can’t expect the tracks to be concerned about how others are doing. Except, it is extremely short-sighted in the face of declining foal numbers, field sizes, participants, handle and attendance — all of which threaten to swamp the entire boat.

But then harness racing sees the big picture about as well as Mr. Magoo.

Post time drag is a clear example. While the sport in its individual two-minute action segments is as compelling as ever, an entire card of racing has become a bloated, completely unwatchable falsehood that serves to aggravate customers and participants alike in the supposed aim of handle growth.

While other sports have actively worked to decrease the length of their events, harness racing is bucking that trend, extending its programs to five and six hours and expecting its paying customers — already a dying breed — to just shrug and go along with a perpetual bald-faced lie.

How does anyone think this is a sound business policy?

I’m all about driving handle which is good for bettors and participants and tracks alike. The trouble is, there’s no actual science to back up the oft-heard contention that dragging leads to greater handle; no proof of a direct correlation between the number of minutes past zero minutes to post and the amount bet. Sure, sure some tracks tried not dragging, briefly, and handle dropped. But there are simply too many factors at play influencing handle to determine that was the sole reason for the decline, particularly when tracks have accustomed their customers to expect a drag.

My contention is that if all major tracks educated their bettors and committed long-term to start rolling the gate when the clock hits zero, in due course those who want to lay a bet would find a way to do so.

Otherwise, we’ll see how much is bet in a few years when there are few betting customers left.

Dragging makes even less sense when most major tracks have fat purses not from handle, but either the legislated largesse of casinos or significant government handouts.

Which brings us to the warlords.

If The Meadowlands’ owner Jeff Gural and the United States Trotting Association’s chairperson Joe Faraldo and president Russell Williams truly had the best interest of the sport at heart, they would all put aside petty differences and figure out how to come together to lead.

As it stands, it certainly appears Faraldo and Williams advocate the status quo — which is baffling given the state the sport is in.

Meanwhile, Gural, while certainly well-intentioned to personally fund an attempt to eradicate cheaters, could be less reactionary and more thoughtful before acting. Case in point, I’m torn whether banning people from The Meadowlands that supposedly purchased performance-enhancing drugs will really help without proof said products were actually given to horses.

Where Gural had it right was helping to fund surveillance that led to the horse doping indictments. The wiretaps were invaluable and telling and gutting.

Horsepeople — the vast majority of whom are the honest, decent folks who made me fall in love with harness racing nearly three decades ago — simply have to do more to stop other people from robbing both them and the sport.

Owners can do their part by giving horses to the most honest of trainers and insisting on the utmost integrity and well-being for their horses. That includes saving a percentage of purse winnings to provide decent after-care for all the horses they own.

Everyone should demand better from leadership that for far too long has done far too little to protect horses, level the playing field and advance the collective interests of harness racing. If leadership doesn’t act, get new leaders.

Frankly, four years after the indictments, how harness racing hasn’t found a way to do better is sickening and pathetic and troubling.

Surely, I can’t be the only one tired of it.