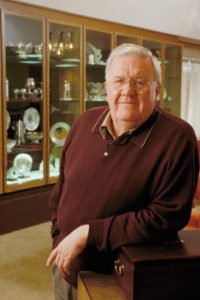

The storied career of Dr. Glen Brown

The highly-decorated former president of Armstrong Bros. has had a rich life in the standardbred industry.

by Murray Brown

There aren’t too many people who have had as storied a career in harness racing as Dr Glen Brown. His accomplishments include, but are not limited to, membership in the Harness Racing Living Hall of Fame in Goshen and the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame; being the former president of the Canadian Standardbred Horse Society (the registration department that was a precursor to Standardbred Canada), a long-time board member of the Hambletonian Society; a former director of the Ontario Jockey Club (precursor to WEG) and head of its standardbred division and most importantly, the former president and face of the Armstrong Bros. breeding empire for many years, one of the greatest breeding establishments in the history of harness racing.

Brown’s dad, James William, was a draft horse dealer in the ‘30s and ‘40s. This was at a time when more people had horses than had cars. He started working for a man by the name of Jack Galbraith of Brussels, ON, who provided him with a train car load of horses to take to northern Ontario to try to sell. By the end of that first day, Jim Brown had sold all the horses and came home to Brussels.

“Where are my horses?” Galbraith said. Brown said they were all sold, mostly to lumber men and miners. He gave him his money.

Jim Brown continued primarily at first with draft horses, but branched out to harness horses and raced them through all the fairs in Ontario and Quebec. He was in Quebec City racing during World War II when Winston Churchill had his famous conference with Franklin Roosevelt.

James Brown became president of the Canadian Standardbred Horse Society (CSHS), Canada’s equivalent of the USTA registration department. It was theoretically a government agency, but it was essentially run and administered by harness people. Several years later, Dr. Glen Brown became head of the CSHS, becoming the second son of a former president to head the society. The only other father/son tandem to have previously done so was the Honorable Earl Rowe and his son Bill.

Jim Brown was one of those involved in starting harness racing at Thorncliffe Park in Toronto. He was the manager, and when the Ontario Jockey Club bought them out and moved harness racing to Old Woodbine, he became the Jockey Club’s first standardbred racing manager.

Young Glen Brown didn’t have much chance but to become involved in the horse business. While attending the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) at the University of Guelph, he worked for the most prominent equine vet at Old Woodbine (later Greenwood) as an assistant. He worked from 7 a.m. to about 4 p.m. After those working hours he took a second job as an attendant in the horse ambulance each evening at the track. He did this for several years. Remarkably, not one single time in those years, was there the need to utilize the horse ambulance.

Upon graduation from the OVC in 1957, there were two things to do: 1. Marry his sweetheart, Pat. 2. Get a job — preferably with racehorses.

Dr. Brown first went to work for Peter Pan Farms in Washington, PA (no relation to the Peter Pan Stable of Bob Glazer).

They stood two stallions — Meadow Gene, a moderately successful son of Adios, and a Worthy Boy trotter named Worthy Aristocrat. Dr. Brown stayed there 11 months. To say he did not enjoy his stay there would be an understatement. It seems that farm owner David Resnick wasn’t the most pleasant person to work for.

He tells the story of the time some people delivering hay were picking up a friend of theirs who worked at the farm. Mr. Resnick arrived and asked Dr. Brown who those people were that were doing nothing.

“You need to get rid of them,” Resnick told Dr. Brown, who responded: “But Mr. Resnick, they don’t work for us” to which Resnick said, “It doesn’t matter. I fired them anyway.”

Dr. Brown remembers bringing the yearling crop to Harrisburg for the sale. On one of the seemingly interminable tunnels on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the truck carrying the yearlings caught on fire. Fortunately, he was in a car trailing the truck. Somehow, they managed to unload the yearlings with no damage caused. The horses made it to Harrisburg safely. That consignment included Dares Direct, one of the early Canadian Juvenile Circuit stars which was purchased by Del MacTavish.

Around that time, Elgin Armstrong was just starting to acquire quality well-bred livestock. Prior to that, his standardbreds were nothing but an ordinary lot and his thoroughbreds were worse.

The first horse he bought from Delvin Miller was a Hoot Mon filly by the name of Helicopter. Armstrong left her with Miller to train. She turned out to be pretty good, winning the Hambletonian for Miller’s assistant trainer Harry Harvey.

There’s an interesting back story to how Miller happened to have Helicopter in his stable at the time.

It seems that Miller and John Simpson had sold a filly to Fred Van Lennep. After awhile, Simpson asked Miller where the money for the sale was. “I’ll have to ask Freddie,” Miller said. Van Lennep suggested that instead of cash, they use the money as credit for buying one of Castleton’s fillies. They bought Helicopter and the partners decided that Miller would train her. There is yet another back story to the filly’s name. She was named Helicopter because Mrs. Van Lennep was transported in a helicopter to deliver one of her children.

That winter, Elgin Armstrong, whom Miller had never met, stopped by Miller’s stable at Ben White Raceway and asked Miller if he had any good fillies to sell. Miller mentioned Helicopter, but said that he had a partner whose permission he would need. Miller called Simpson and told him he had this Canadian to whom he could sell their filly for a fair price.

“Hell, yes,” Simpson said. ”You never can go broke if you take a profit.”

From that point on, Miller was the Armstrong brothers’ main trainer. They also had Harold McKinley, who trained and raced the horses that weren’t quite Grand Circuit stock in Canada. Jimmy Takter, Chuck Sylvester, Jack Kopas and Bill Wellwood also trained some on occasion.

Dr. Brown isn’t one hundred percent sure, but he believes that it was Miller who recommended him to Elgin Armstrong to be their vet and farm manager.

Dr. Brown met Elgin and was hired.

“What a pleasure to finally work for some reasonable people,” Dr. Brown said.

When Dr. Brown arrived at the Ontario nursery, things were somewhat in turmoil. The 300-acre farm was infested with strangles. About 20 of the mares were thoroughbreds that weren’t much. The standardbred mares numbered around 15. They were a little better, but not a whole lot. Dr. Brown recommended that they sell all the thoroughbreds and most of the others.

With Dr. Brown’s urging, Elgin Armstrong decided to concentrate on quality. The apex of quality at that time were pacing mares by Adios (who he called Adioo) and trotting mares by Hoot Mon. The majority of the fillies and mares they concentrated on in the early years were by those two stallions. After all, two of the first horses they bought were Dotties Pick (Adios) and Helicopter (Hoot Mon). At one time, Armstrong Bros. owned 22 mares by Adios.

When one considers the passage of time, arguably the greatest pacing filly ever was one of those Adios mares. Her name was Countess Adios. She completely overwhelmed a good crop of colts as a 3-year-old. She raced free legged. She demolished the colts in the Cane and the Messenger and would almost certainly have also won the Little Brown Jug had she been eligible. He raced Countess Adios in partnership with Hugh Grant, but the deal was once she was retired, she would become a member of the Armstrong broodmare band. The Armstrongs also owned a sister or two to her. Miller had a yearling colt out of her dam, Countess Vivian, who he offered to Elgin Armstrong. Assuming that the colt was by Adios, he was interested. When he found that the colt was by Dale Frost, he lost interest. That colt was Meadow Skipper.

After a few years, Armstrong Bros.’ ABC Farms became one of the sport’s breeding behemoths.

In the early 1970s, Glen Brown was part of one of the many groups trying to get the Ontario government to fund a Sires Stakes program. He was appointed a member of the Ontario Racing Commission in 1973 and served there for 11 years. The Commission immediately formed the Ontario Horse Racing and Breeding Advisory Committee and made Brown its chairman. It had representation for the breeds, the tracks and the horsemen’s associations. They were tasked with designing and implementing a program. The program has been highly successful and has saved the Ontario Industry, In 1989, The CSHS honored Dr. Brown with its Achievement Award.

Shortly after concluding his Commission time, he was elected a director of the Ontario Jockey Club, later to become Woodbine Entertainment. (WEG). He served on that board for a number of years, including as chair of its standardbred committee.

When Dr. Brown first came to work at Armstrong Bros. they were selling their yearlings at Harrisburg. He was instrumental in establishing the first Canadian select yearling sale to be run by the CSHS.

Most people believe the Kentucky Standardbred Sale was the first to be a “select” sale that physically evaluated the yearlings nominated. They were not. The first one was the one established in Canada by Glen Brown.

One year at Harrisburg, when Elgin Armstrong had a decent consignment, their horses were sold first thing in the morning. They believed they were negatively affected by the forward placement in the sale. The next year, Alan Leavitt was starting a new sale at Liberty Bell. The Armstrong yearlings sold there for a few years. One year, Leavitt told Dr. Brown that he was going to sell his Lana Lobell, Speedy Crown yearlings at his New Jersey farm to coincide with Hambletonian weekend when many European buyers were expected to be present.

“What about us and the other consignors?” asked Dr Brown. “Oh, I’ll continue the Liberty Bell sale,” said Leavitt. That would have been the equivalent of taking Hanover yearlings away from Harrisburg. This obviously did not sit well with Elgin.

“We grew tired of being manipulated by the sales companies,” Brown said. “We wanted a say in our destiny. Tom Crouch and Bill Shehan had started the Kentucky Standardbred Horse Sales Company and we looked into selling there, but only if we could buy into the enterprise and have some say as to how we were handled. They sold us and Jack Baugh (Almahurst Farm) each 24 per cent, with Crouch and Shehan each retaining 26 per cent. From that point forward, we sold all our premier yearlings there.”

One year at Harrisburg, Miller told Dr. Brown and Elgin that he needed to cut down. Dr. Brown had just given him a list of the yearlings that they were keeping to train. One of the ones that Miller had commented on was the Helicopter filly. “Maybe you ought to give her to someone else to train. I haven’t had much luck in training her foals,” Miller said. “Besides, I really need to cut down and start enjoying life.”

Elgin asked him who he would recommend to train. Miller said that Joe O’Brien had just become available. He was the contract trainer/driver for the Camp Stables. Sol Camp had passed away and after a couple of years in the business, his son Jim had just sold all the horses and their farm in Kentucky. “He’d be a great trainer for you,” Miller said.

They met with O’Brien at Harrisburg and the horses were placed in O’Brien’s care. That Stars Pride filly out of Helicopter that Delvin had referenced turned out to be Armbro Flight, who Glen Brown believes was the greatest horse ever raised by Armstrong Bros.

“One thing about Elgin,” Dr. Brown said. “He believed in always having good people working for him whether it be in the construction or the horse business. Jimmy Hammond and Larry Drysdale were two of the very best people I’ve ever known when it came to raising and prepping yearlings.”

Elgin Armstrong noticed that they were racing for pretty good purses in California, so he suggested that Dr. Brown send some there to race. They sent a few from their Canadian stable to Howard Beissinger. The best was a pacer by the name of Fast Buck. He did pretty well, which prompted Beissinger to ask, “Do you have any more like those to send to me?”

Elgin bought a place in Florida where he would spend the winter. He decided to give a few to Billy Haughton so that he could keep his interest piqued by being near his horses. The very first one was an Airliner colt by the name of Armbro Omaha, a grandson of Countess Adios. As with Miller and Helicopter and O’Brien with Armbro Flight, it wasn’t a bad way to begin. Omaha became the first standardbred to win five $100,000 races in one year.

After Elgin and brother Ted died, the Armstrong Bros. equine enterprise was left in somewhat of a state of flux. Elgin’s son Charlie had some interest, but initially his main interest was with jumpers and show horses. He gradually acquired some standardbreds and began to raise his own, in addition to having his name on the masthead of Armstrong Bros. Through the years, he achieved significant success with Bill Wellwood training and driving for him. There were other members of the founding family who didn’t have the equine interests that Charlie had. The construction company had been sold. There were some among the heirs who felt that the same should be done with the horse enterprise. Thus the seeds of the demise of Armstrong Bros. as a major force in world-wide breeding were sown.

What about Albatross? You guys were in the original syndicate organized by Alan Leavitt, then you sold out after the excrement hit the fan and the horse was re-syndicated with John Simpson running the show?

“There has always been somewhat of a misunderstanding regarding those events. Firstly, Armstrong Bros., the corporation, was never a principal in Albatross. For business reasons, Elgin and Ted were as individuals. We all felt, rightly or wrongly that physically Stanley Dancer was in no position to train and race a horse in which we had a large investment from a hospital bed. It was somewhat incongruous to have an ambulance show up at the paddock and unload Stanley to race him. Things got pretty nasty and Elgin and Ted decided that it would be wise to just get out. A good offer was made, so that is what they did.”

The year was 1979. Dr. Brown was in Harrisburg with Charlie Armstrong, Bill Wellwood and Glen Garnsey. Armstrong had budgeted $300,000 to spend on yearlings. They had bought Delmegan and a high-priced Steady Star filly. Delmegan was given to Garnsey to train. “We are all spent out,” Charlie said of he and Wellwood.” We are going home.”

Dr. Brown decided to stay at the sale with Garnsey. Hanover was selling in a night session. Dr. Brown was looking for an Albatross filly to become his future broodmare. They were very much in demand and brought some hefty prices. There was a filly in the ring not bringing much money. Dr. Brown had seen her, but Garnsey had not. Dr. Brown recalled Wellwood telling him that he had been to Hanover and had seen the filly. Dr. Brown remembers Wellwood telling him, “She could fly on the pace alongside the lead pony. She was small, but could she ever go.” When the filly was in the ring, Dr. Brown bought her with one bid at $20,000. He said to Garnsey, “You’d better go take a look at her.” Other than being quite small, she was well put together. Garnsey said, “She’s too small to breed as a 2-year-old. Why don’t you ship her to Florida and we’ll see what we’ve got?” The filly’s name was Fan Hanover. She turned out to be one of the great pacing fillies ever. She was Horse of the Year in 1981 and is still the only filly to ever win the Little Brown Jug.

At the age of 71 in 2004, Dr. Brown decided that it was time to lessen his work load and semi-retire. Dr. Moira Gunn was named the Armstrong Bros.’ president and farm manager.

She called her mother in Scotland to give her the news. “I’ve got both good news and bad news,” she told her mom. “The good news is that I’ve become the president of Armstrong Brothers. The bad news is that they will be going out of business fairly soon.”

The sad fact was that there were quite a few heirs to the Armstrong fortune and very few of them had any interest in harness racing.

The decision was made to sell all the horses and the farm.

It was a melancholy time for those who had given so much for the farm’s success and its place in history.

Dr. Glen Brown is now 87 and lives self-sufficiently in a condo in Brampton, ON.

“I don’t expect to live forever,” he said. “This old body is showing its age. I still get around, albeit with the aid of a walker. My family visits often and I really enjoy my time spent with them. I still follow the horses. Normally at this time of year, I used to be in Florida where I leased a condo. But COVID-19 has dashed all those plans. All in all, I consider myself a pretty lucky guy, who has lived a great life.”

Have a question or comment for The Curmudgeon?

Reach him by email at: hofmurray@aol.com.