My summers as a swipe – Part 1, 1966

by Dean A. Hoffman

After my final two years of high school and my first two years of college, I spent the summers working at the bottom rung of the ladder in the horse business. I took care of horses, first on a breeding farm and then on the track.

What I experienced stays with me even today, although these were years in the late 1960s when America was experiencing racial strife and protests over the war in Vietnam.

In harness racing, however, there was nothing but optimism then. There’s no such thing as a sure thing in horse racing, but we knew in the late 1960s that harness racing would get bigger and better every year. It had been that way since the end of World War II in 1945.

In that sense, the late 1960s were a vanished world for harness racing. The scourges of off-track betting, state lotteries, simulcasting, and racinos had yet to give gamblers choices that threatened the basic business model of racetracks.

It was indeed halcyon era.

This is the first in a four-part series in which I relive my education and experiences as a groom (I prefer the old term “swipe” in the headline) over four summers from the distant past.

“Here, boy, you might as well learn the horse business on the end of one of these.”

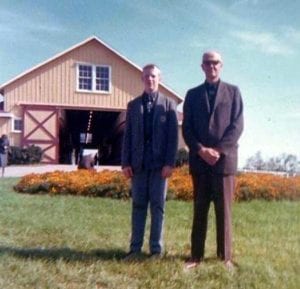

With those words in June, 1966, Ted Woodley, the manager of Walnut Hall Farm, introduced me to four summers of caring for horses, first while in high school and later college.

I was a suburban kid from Cincinnati. I knew a crouper from an overcheck and I knew that straw was yellow and hay was green. But that was about all I knew about the practicalities of horsemanship.

My learning process did indeed begin on the end of a pitchfork. At times I thought it would never progress beyond that point. It seemed that I spent at least three weeks at Walnut Hall Farm cleaning stalls.

I was paired with two brothers from Louisville who were of similar age. We were the greenhorns just there for a summer job before school started. We lived together in a small room above the broodmare barn office. That was just a stone’s from the historic stone stallion barn where Volomite and Scotland reigned for many decades. Not far away was the statue of Guy Axworthy near the farm’s graveyard of greats.

At time I thought that some of the stalls at Walnut Hall had not been cleaned since Guy Axworthy died at age 32 in 1934. I had come to Walnut Hall with visions of being around famous horses, but the routine of cleaning stalls never seemed to end.

The evenings, however, were mine, and I could roam among the broodmares in the endless pastures. There was Impish, the feminine bay that made history as a juvenile five years earlier. There was the dark Emily’s Pride, winner of the Hambletonian just eight years earlier and already the dam of the wunderkind colt Noble Victory.

I secured my summer job because my father knew Ted Woodley, the manager, and dad was also close to Cincinnati owner Sam Huttenbauer, who was close to Katherine Nichols, who owned Walnut Hall. My responsibilities consisted of 12-1/2 days of work every two weeks. Every other weekend I got off from Saturday noon until Monday morning.

For my services, I was paid $75 every two weeks (minus deductions, of course). But the farm provided me with a place to live and I took my meals at the farm’s boarding house, a tradition that now seems quaint but then was simply part of farm life.

In fact, my first day gave me an introduction to boarding house etiquette and taught me a valuable lesson on seniority.

Farm hands gathered in waiting room in the boarding house until one of the cooks rang a bell to indicate the food was ready. We waited on ancient couches, a few hardback chairs, and one or two easy chairs. I arrived before lunch and took the most comfortable chair.

I noticed that some of the farm workers looked at me with a smile or slight snicker, but I wrote that off to the fact that I was the new kid on the farm, just a teenager among much older, experienced men.

As I waited, a stooped old man walking with a cane approached me, stared at me with absolute disdain and disgust, then exploded like Mount Vesuvius with a torrent of mumbled profanities. When he began shaking his cane at me, I shot up out of that chair like a Jack-In-The-Box as I heard and saw snickers from others in the room.

It seems that on my very first day, I had committed the unforgivable sin of sitting in the easy chair of George Johnson, a bent-over pensioner who had earned certain privileges with decades of seniority.

From that day forward, I never even got within a few feet of the old man’s easy chair and never dared to speak to him. I was much younger, a foot taller, but he always carried that cane and scared the bejesus out of me. I gave him a wide swath.

If I had been smarter, I would have befriended George Johnson because he had lived an absolutely amazing life in the harness horse world and I could have learned so much from him. But then I just saw him as a crabby old SOB to be avoided at all costs.

George Johnson was born in 1879 and spent his entire life with horses. When I encountered him, he was 88 and had been a pensioner at Walnut Hall for almost two decades. But in 1912 he had been among the grooms that accompanied the C.K G. Billings horses for exhibitions in Czarist Russia. Johnson sailed with the Billings’ troup to Hamburg, German, then took a train into Russia.

Later in life, Johnson came to Walnut Hall to work as a stationer and in that role he cared for such stalwarts as Peter Volo and his son Volomite and the rugged Scotland.

Eventually, I was experienced enough to be trusted handling broodmares as they were bred or checked for pregnancy. I remember sitting on the tailgate of a pick-up truck that summer leading the mares Beloved and Cheetah Goose behind me. Beloved’s daughter Kerry Way would win the Hambletonian that summer and Cheetah Goose had a good son named Bullet Van that roughed it up it with Bret Hanover.

I was also thrilled to find myself working alongside Donnie Miller, a top-notch trainer and driver who had steered Bret Hanover to his freshman record of 1:57.2 just two summer previously. Donnie was experiencing some health issues that kept him away from the racing wars, but he pitched right in with the know-nothings like me to help with the Walnut Hall breeding stock.

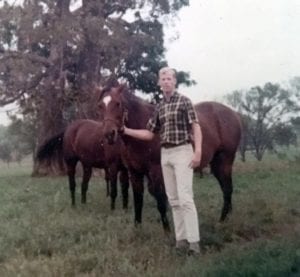

Perhaps the most significant friend I made that summer was Phil Straw, a fellow Ohioan who was finishing up his college education at the University of Kentucky. He had fallen in love with harness racing as a young teen, as I had, and made Walnut Hall his home in the summers and later when he was a full-time student at UK. He lived in a little cabin near the foaling barn which he called The Ponderosa.

Inviting me into his abode, Phil pulled out a box that was chock-a-block with harness racing treasures and mementos. He had a shoe worn by Hickory Smoke when he won the Hambletonian nine years earlier. Phil had a photo of him with Adios Butler when the pacer set the world record for pacers on a half-mile track at 1:55.3 in a time trial five years earlier.

I was both fascinated and envious and asked Phil, “How’d you get all this stuff?”

“Wrote the owners,” he said simply. “They appreciate it when someone shows a genuine interest in their best horses and they’ll usually send you something.”

I filed that information away and later that summer I wrote a letter to Norman Woolworth, owner of Meadow Skipper, who was then completing his first season at Stoner Creek Stud in Paris, Kentucky. I admired Meadow Skipper because I knew he was troubled by splints and yet gritted his way past the pain to have a successful race career. At my high school, I competed on both the cross-country and track teams and was hampered by shin splints. (I was also hampered by a lack of speed.) That letter to Woolworth was my paean to Meadow Skipper.

Woolworth responded by sending me photos not only of Meadow Skipper, both also of other stars from his stable. That led to a friendship of almost 40 years with Norman and I was honored to speak at a memorial service for him at the Harness Racing Museum in 2003.

Walnut Hall is truly the grand dame of standardbred nurseries, having been established 1892 with the money Lamon V. Harkness made from his association with Standard Oil. It was a magisterial Bluegrass estate with sweeping and seemingly endless fields of bluegrass.

Other trotting nurseries came and went over the first half of the Twentieth Century but Walnut Hall endured and the business of breeding horses carried on through several generations of Harkness descendants.

It was truly the dominant breeder of that era and its old stone stallion barn housed such legends as Guy Axworthy, San Francisco, Peter Volo, Scotland, Volomite, Guy Abbey, and Demon Hanover. Countless Walnut Hall broodmares contributed immeasurably to the breed.

The stallion roster when I worked there in the 1960s, however, consisted of a now-forgotten brigade of well-bred wannabees. Among them were The Intruder, Storm Cloud, Saboteur, Uncle Sam, Duane Hanover, Coffee Break, Adios Paul, Kimberly Kid, Trader Horn, etc. In retrospect, the stallion roster looked like a losers’ convention.

When Castleton Farm, located just across Newtown Pike, stood Good Time, Speedster, Florican. Worthy Boy, Speedy Scot and other prominent stallions, Walnut Hall’s line-up played second fiddle.

Perhaps the sudden demise of Demon Hanover chilled farm owner Katherine Nichols’ desire to invest heavily in a single stallion. Walnut Hall had participated heavily in the syndication of Demon Hanover for $500,000 in 1958. The intelligent and talented stallion was moved from his base in Ohio to Walnut Hall and ensconced in the stall long occupied by Volomite. (No pressure there.)

Demon Hanover bred one book of mares at Walnut Hall in 1959 and died suddenly that fall. The hopes and dreams — not to mention a lot of money — of his shareholders went into the ground with him. Seldom again was Walnut Hall a force in acquiring the best young stallions in the breed.

The Walnut Hall stallions of the mid-1960s, despite commendable accomplishments on the track left a very limited legacy to the breed.

I came to know them as individuals with the expected quirks in the breeding shed. Coffee Break was small and short-legged, as were many of the get of Good Time. He was so short that he had difficulty mounting mares at time, so a small mound was built into the corner of the breeding shed. Coffee Break would stand there when he mounted mares and, as a result, we called that mound “Mount Coffee Break.”

Kimberly Kid, a sensation on the track and considered as “the last of the Volomites,” had a weak hip and hind end. When he mounted a mare, David White, a burly son of the Kentucky hills, would put his shoulder under Kimberly Kid’s hindquarters to give him support during breeding.

Most of the breeding was done by live cover. Because I began work after the school year was over, much of the breeding season was over. Invariably, miscues occurred in the breeding shed. I recall seeing Duane Hanover breed a maiden mare named Ensign’s Delight. She was so startled when she felt the stallion on her back that she collapsed and fell to the ground, almost taking her paramour with her.

Artificial insemination was practiced in the most rudimentary fashion. Stallions were fitted with condoms (“equine breeding bags” sold by a firm in Crestline, Ohio) and the semen was collected. It was then poured into cups and delivered to a mare to be inseminated. I recall assisting in such efforts and riding in a pick-up truck with a cup of semen sitting on the dashboard.

In the evenings after work at Walnut Hall, I loved to walk up to the cemetery were so many legends of the breed rested for eternity, with the statue of Guy Axworthy standing sentinel over them. Stones marked the final resting places of Volomite, Scotland, Peter Volo, Demon Hanover, Guy Abbey, and many important and influential broodmares.

I recall a towering oak with roots at its base that provided me with a comfortable spot to sit and read, looking out over the sweeping Bluegrass pastures.

At the end of August, it was time for me to return to Cincinnati and start my senior year in high school. But I was already planning another summer amid the boundless beauty of Walnut Hall Farm.