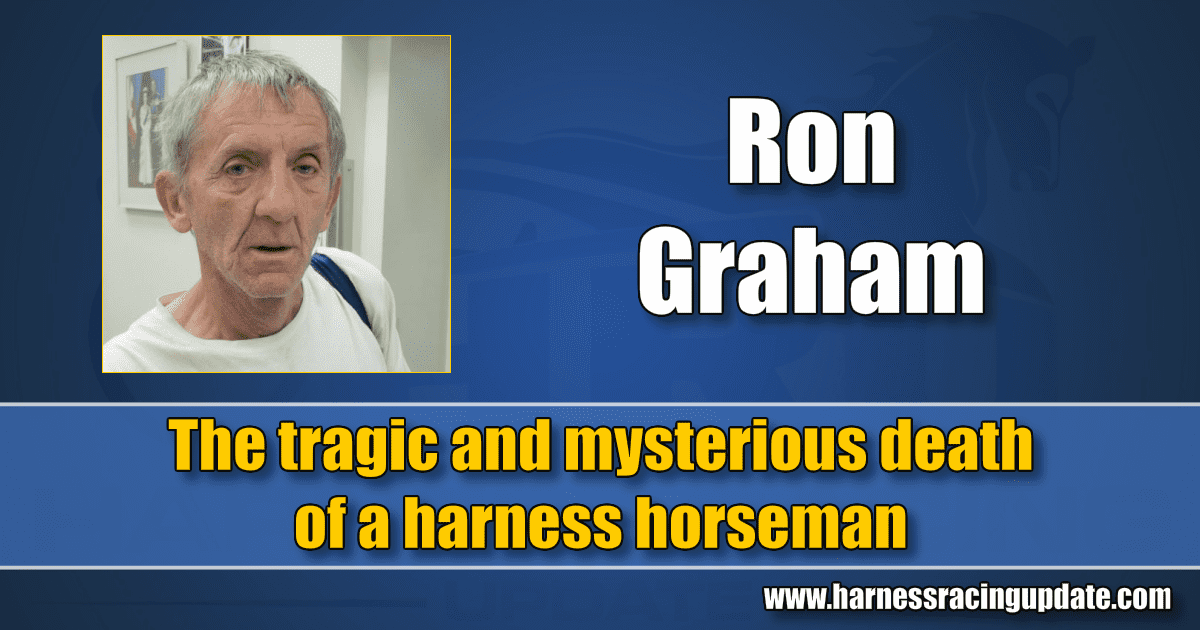

The tragic and mysterious death of a harness horseman

Ron Graham’s body was found on the streets of Toronto.

by Melissa Keith

In a sport where memorial races and commemorative awards are the norm, it seems bleakly ironic that a former horseman can die alone and forgotten. But this was the fate that befell Ron Graham, who ended up homeless in Toronto. The Cape Breton-born trainer/driver passed away sometime during the night of October 27, 2018. His body was discovered the next morning, inside the gates of the Osgoode Hall legal building. He was 62.

Graham was not friendless, despite the hardship of his living conditions. But his companions were living rough themselves, ill-equipped to help each other get back on their feet. Many, like Ron, were clients of Haven Toronto, Canada’s only drop-in centre for older (50+) homeless men. Lauro Monteiro, Haven’s executive director, recalls getting the disturbing news. The morning of October 28, other people sleeping rough near Osgoode Hall “were just getting ready for the day. (Ron) wasn’t moving or getting up. One of our guys called 911, but he was already deceased.”

The official record has scant details of Ron Graham’s life. His career in harness racing predates the era of ready digital data availability, although it seems that he played a valuable role behind the scenes, working as a groom and possibly a trainer or assistant trainer at major tracks.

“Here in Toronto, there were two principal racetracks,” said Monteiro. “He worked at both Woodbine (harness) and Greenwood. He spent a good deal of time at Blue Bonnets.”

Greenwood Raceway ceased racing in 1994; Blue Bonnets/Hippodrome de Montréal followed suit in 2009. Yet Graham’s freefall cannot be attributed to the closure of any one racetrack, nor to the end of Ontario’s Slots at Racetracks Program in 2012.

Graham once declined Monteiro’s offer to directly contact any old connections back home, making a different request instead. “When I went to Cape Breton, he told me to bring him a lobster, and I did—and he threw it at me, because it was plastic,” said the Haven administrator, who frequently joked with Ron and considered him a friend. Exchanges with a number of prominent Cape Bretoners in harness racing—including the unrelated Northlands Park trainer/driver Ron Graham, who is happily retired and living in Edmonton—suggest that the late Ron Graham came from a racing family in the Sydney, NS area.

“When I arrived in 2010, he was outside, sleeping rough. He was very popular with a lot of our guys who are into gambling, which gradually slowed down after a while,” said Monteiro. Fewer clients with connections to the tracks come through the doors at Haven now, he adds, pointing out that people in any profession can find themselves on the streets due to many varieties of personal misfortune.

Graham’s premature death was entirely preventable, and nearly prevented. “It was so, so, so sad. It counters the stereotypes: Ron really struggled for a couple of years to try and find a safe space and be around a community of people. That’s really important,” said Monteiro. After a lengthy wait, Graham landed a Toronto Community Housing apartment. “So Ron got a place out in the west end of the city. At first, he was happy, he loved it. Then things started to go a little wrong in the area—drugs, prostitution—and he absolutely hated it.”

The retired horseman requested a new place to live. “For safety reasons, (Toronto Community Housing) can relocate people, especially older people,” said Monteiro. “They tried for over a year to relocate him. He was becoming increasingly despondent as time was going on.” The situation reached a breaking point for Graham: “It wound up that his downstairs neighbour burned her apartment down, but they wouldn’t evict her, so he grabbed the little possessions he could and walked away, to sleep rough.”

Monteiro said Graham refused to use homeless shelters. “Ron hated those places because they are very unsafe and older men are victimized there. He wouldn’t go in.” But the alternative was also cruel: “He was sleeping under one of the overpasses and he was robbed. He was so thankful that they stole his cell phone and everything, but they left his medication.” Graham would visit Haven’s Jarvis Street drop-in each day to play cards and share stories of happier times.

“He was one of the most humble guys I ever met in my professional career. Outwardly, he was very tough and streetwise. I sort of gravitated to him for a whole lot of reasons. I thought, ‘Let me keep an eye on him,’” said Monteiro. But far from being a troublemaker, Graham revealed himself to be a quiet helper to those worse off than himself.

“He wasn’t a jockey, but he looked like one. Wiry like you wouldn’t believe. I wouldn’t want to get into a fight with him, but he had a heart of gold,” explains Haven’s executive director. “I can’t tell you the number of times Ron came up to me and said, ‘Look, this guy won’t tell you, but he needs this or he needs that.’” Monteiro remembers how the former “chariot-racer” brought winter boots to a homeless Korean War veteran who rejected anything that resembled charity: “This guy will not take even a free cigarette from you. He will buy one from you. He will not take anything, but he took the boots from Ron and he wore them.”

In the days before his death, staff at Haven noticed that Graham wasn’t himself. Monteiro said Graham refused to be taken to hospital, and may or may not have sought medical attention on his own. As always, he turned down offers to help get in touch with his family.

“He had a niece, now deceased, and a sister in Cape Breton. It’s not unusual to have family in other parts of Canada and not to have talked to them in years. There’s a lot of stigma with older people. A lot of the guys, they don’t want their families to know (they are homeless). He was very proud of what he did for a living, his skills and accomplishments in that field.”

How Ron Graham ended up on the streets is a mystery, which might be what he intended. “I don’t know whatever happened in terms of how his life fell apart, but when he talked about Blue Bonnets, he was very proud,” said Monteiro. “He had names, he knew everybody. He was always very animated when he talked about it. I never went to a horse race in my entire life, so it was nice to listen to him. You could just tell he loved it. He was so passionate about it.”

There was no obituary written for Ron Graham—in fact, this article was written in an attempt to gather enough information about his life to make an obituary possible. Graham’s passing was marked in December, at the Church of the Holy Trinity’s monthly memorial service for Toronto’s most recently deceased homeless people. It seems tragic that a man with such pride in his harness racing career would disappear into the shame of his situation, erasing his presence among those who could have helped. It also seems that learning more about what happened to Ron Graham might help protect other retired horsepeople from a similar fate. While he avoided the spotlight, it sounds like what he would have wanted.

If you remember Ron, feel free to contact Lauro Monteiro at Haven Toronto: (416) 366-5377, info@haventoronto.ca, or Melissa Keith (mkeith71@gmail.com). Donations in his memory can be made at www.haventoronto.ca.