Breaking “the grip of the devil”

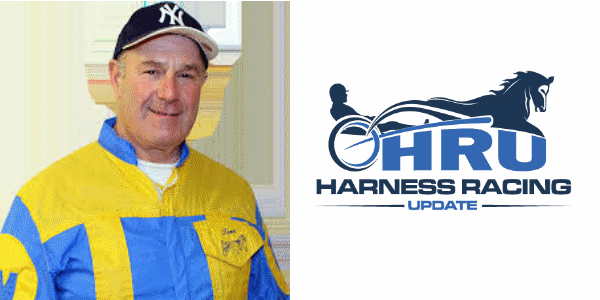

Substance abuse and a suspension of his racing license nearly ended the career of Thomas Milici, but sobriety has played a role in the 61-year-old’s jump to the top of the Yonkers trainer standings.

by Tom Pedulla

Thomas Milici has freed himself from what he describes as “the grip of the devil” to become one of Yonkers Raceway’s leading trainers at the unlikely age of 61.

Milici’s reference to the devil is his way of describing the ruinous hold alcohol and substance abuse had on him, leading to the indefinite suspension of his license on June 1, 2008 after he tested positive for cocaine. He said he has maintained his sobriety since Aug. 4, 2010, and is now taking his career to heights that were once unthinkable.

As of April 21, he had already set a career high for victories (60) – more than doubling last year’s total of 27 — and earnings ($5834,670). His previous mark for wins was 44 in 2005. He shattered his personal best for earnings of $304,020, set in 2015.

To Milici, entering the twilight of his career does not have to mean the downturn that occurs with many trainers. In his case, he is doing everything he can to make up for lost time.

“The body is getting there,” he said of his senior years. “But in my mind, I still feel like a kid.”

Milici said his eye-opening results reflect the mental clarity he has enjoyed since he put down his final drink and did his last line of cocaine. He said his years of abuse involved alcohol much more often than drugs. Whatever the case, the combination took a staggering toll on his personal life and his career.

“It’s a lifestyle where you are not the person you can be or should be,” he said. “You might show up to work, but you’re not there. You’re there physically, but not mentally.”

To Milici’s credit, he was the first to raise the issue of his personal misconduct during an interview, perhaps demonstrating how far he has come. His license was revoked in New Jersey in 1991 for “financial irresponsibility.” He was convicted of driving while intoxicated in 1998 and 2005. Delaware denied his application for a license in 2002 after one of his horses recorded a post-race positive. He was fined and suspended for 105 days for attempting to treat a horse on race day.

He points to his indefinite suspension in 2008 as a critical juncture in his personal turnaround. “The best thing that happened was coming up positive,” he said.

Without his daily trips to the barn and his involvement in the sport he loved, he had little choice but to focus on the damage he had done to himself, to his wife, Kathy Tufano, from whom he is now estranged, and his two stepchildren.

Milici recalled his days as a student at Holy Cross High School in Queens, NY when peer pressure would lead him to buy a six-pack with friends but then empty many of the cans when no one was looking because he did not care for the taste of beer. He eventually graduated to vodka and said his alcoholism escalated after he turned 50.

“Vodka kicked me to the curb,” he said. “It changed my personality. You hurt the people you love.”

Mal Burroughs, owner and driver of 1997 Hambletonian champion Malabar Man, is Milici’s brother-in-law. Milici introduced Burroughs to his sister, Janet. Burroughs describes Milici as being “as caring as you can get.”

As damning as Milici’s background is, his softer, gentler side was not lost on others. It led high-powered trainer Jimmy Takter to hire him as an assistant in 2011 following his emotional plea to racing officials to end his suspension and permit his return.

Milici has advised racing authorities in New York, New Jersey and other nearby states that he is available to speak to others who are involved with alcohol or substance abuse with the hope of pointing them in the right direction. He said he has, in fact, mentored others.

The native of Brooklyn, NY remains devoted to Alcoholics Anonymous and deeply appreciative of what the program provides for him. “It teaches you really how to live,” he said, “and it’s a great way of living. One day at a time.”

Milici feels well-equipped to deal with any temptation to relapse. Help is a phone call or meeting away.

“Relapses happen, but they say it’s not a requirement,” he said. “You think it through. What do I have to do that for?”

According to Burroughs, Milici had long been his own worst enemy, a seemingly helpless cause. “I helped him out a lot and I was upset with him, to say the least,” he said. “I probably didn’t talk to him for a year.”

Burroughs is convinced Milici’s sobriety will be lasting. “I feel confident he’s on the straight and narrow in his personal life and in his training life,” he said.

Neal Rosenberg teamed with Milici to enjoy a successful run with Happy Gennaro in the early 1980’s. He was much more than a client, however. He describes himself as the “Jewish member” of Milici’s family. When Milici needed to confide in someone, he was there to listen.

“He was self-destructive,” Rosenberg said. “I don’t know all of his demons, but I believe he’s defeated his demons. His current success reflects that.”

Milici’s horsemanship has never been questioned, and Takter’s willingness to hire him surely serves as a testament to that. Milici urges his assistant, Kevin Efimetz, and other members of his staff to speak the language of those under their care in a 25- to 30-horse stable built primarily on claiming horses. Major Athens, a six-year-old trotter who represents a shrewd $65,000 purchase at the Meadowlands sale last January, leads the contingent.

Howard Taylor, an attorney based in Philadelphia, sent horses he owned to Milici 15 years ago. He decided to give him another chance once Milici left Takter to resume his own operation.

“I was expecting good,” Taylor said of the results. “But not nearly this good.”

Other than to attempt to mend fences with loved ones wherever possible, Milici tries not to look back.

“Of course, I have regrets. I do think about it,” he said. “There are consequences for our decisions. There are rewards for our decisions.”

He is ecstatic to finally reap rewards from the right decisions. As of April 21, he led all Yonkers trainers with a 37 winning percentage and a UDRS of .500. He admits to being astounded by his soaring comeback.

“This is against the odds,” he said. “It’s not supposed to happen.”

But it is happening. One day at a time.