Gone but not forgotten

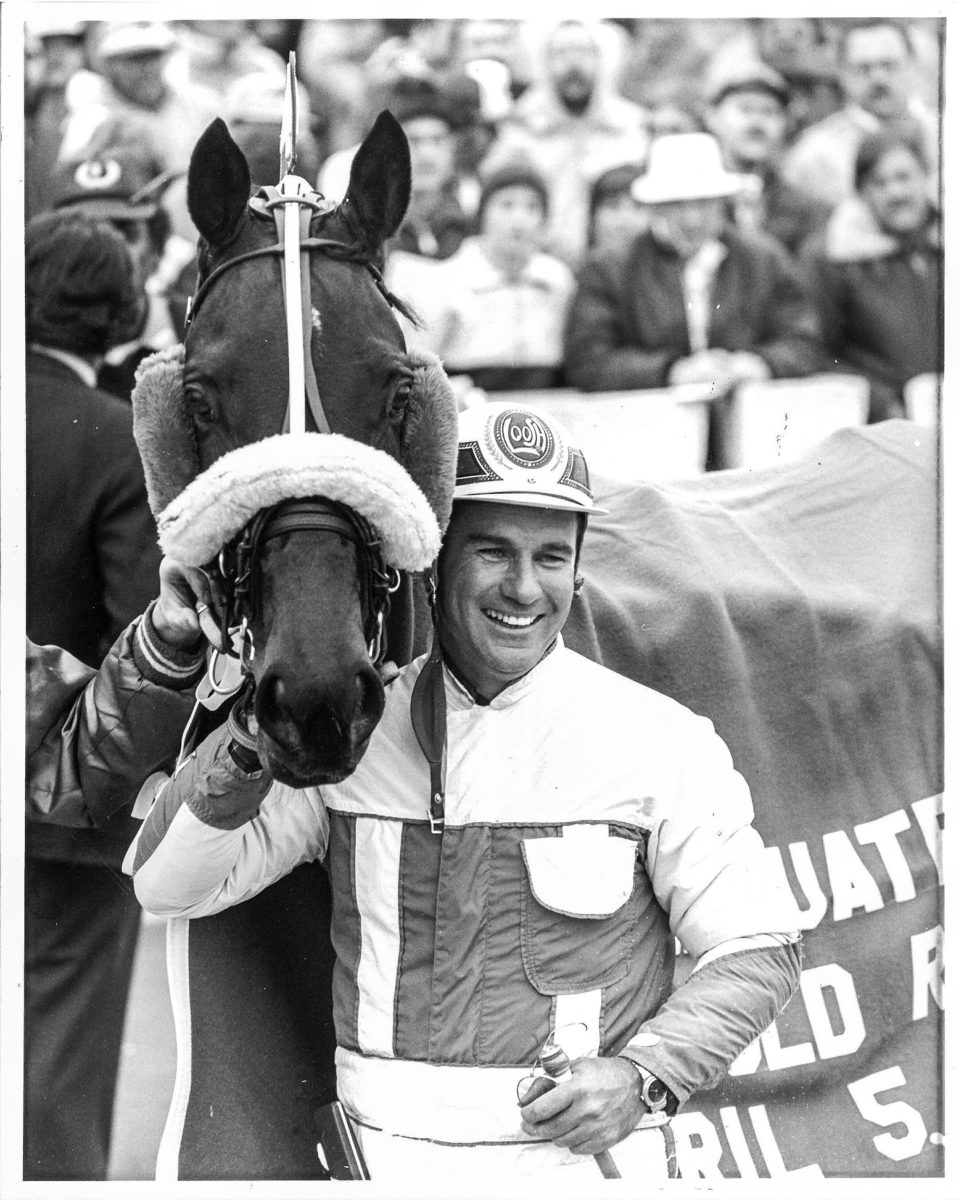

Lucien Fontaine will finally be inducted into the Hall of Fame, albeit posthumously.

by Debbie Little

When asked in July of 2022 how it felt to get the call about being elected to the Hall of Fame, Lucien Fontaine said he was very happy.

“I almost didn’t think I’d live to see it,” Fontaine said with a laugh. “It feels great. I can’t wait to go to Orlando in February [for the Dan Patch awards] and to Goshen in July. I didn’t get here on my own and I have a lot of people to thank.”

Unfortunately for Fontaine — and harness racing, for that matter — he died unexpectedly in September of last year and never got to revel in or truly celebrate his Hall of Fame election and induction.

His quotes in this story, unless otherwise specified, are from that July interview.

Fontaine said in addition to the horsemen — especially Keith Waples, Clint Hodgins and Forrest Bartlett — that helped him along the way, he also appreciated those writers that never forgot him.

Since Fontaine last drove 34 years before his HoF election, he felt that he may have been a little forgotten by some but said he knew there were a few members of the U.S. Harness Writers Association that supported him and continued to nominate him.

When asked why he thought he wasn’t elected years ago like some of his contemporaries, such as Carmine Abbatiello, Buddy Gilmour, Del Insko and George Sholty, he said he really didn’t know.

“All I can think is once you step out of the spotlight, they forget about you,” Fontaine said.

In 2014, The Meadowlands played host to a Roosevelt Raceway Reunion that both Abbatiello and Fontaine attended.

Fontaine talked about the epic battles he and “The Red Man” had and about how good it felt when he made it to the wire first.

“When I beat Carmine, I knew I did well, and I think he felt the same way,” Fontaine said.

When asked if he thought Fontaine should be in the Hall of Fame, Abbatiello looked at him and smiled and said with a laugh, “I guess so.”

He went on to explain that he and Fontaine should be there together, just like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

In July of 2022, Fontaine said what may have hurt his chances in the years following his retirement was that the game changed and drivers got so many more opportunities.

“You can’t compare what we did then with what they do now,” he said. “The numbers I had were good but they don’t stack up with what guys can do now.”

For example, in 1968, Fontaine had 264 wins (from 1,359 starts), ranking him second in North America. Currently second this year is Ron Wrenn Jr., who has 343 wins (from 1,305 starts), and it’s only the beginning of July.

Looking back on his career, Fontaine was appreciative of all the opportunities that he’d been given. Although it was sometimes tough going as the one recognized with being the first official catch driver.

“Being a catch driver was not the same back then,” Fontaine said. “They didn’t have to pay you the 5 per cent if they didn’t want to. I can’t tell you how many drives I did for ‘free.’ It wasn’t right. You can ask any of the guys that drove back then and they’ll tell you the same thing.

“With so many catch drivers today, I can’t imagine how they’d feel if they didn’t get paid.”

Fontaine was on the board of directors of the Standardbred Owners Association of New York and was the driving force responsible for getting the 5 per cent driver’s commission taken out by the track. He said he knew of a similar practice that was in place for thoroughbred jockeys and that’s where the idea came from.

He was also a member of the New York State Racing Commission’s rules committee and fought hard for pre-race testing for both standardbreds and thoroughbreds in New York, as well as getting long-term insurance and pensions for horsepeople.

“I just wanted to do what I could to help guys that weren’t as fortunate,” Fontaine said. “Harness racing was good to me and I wanted to be sure it was good to others, too.”

Fontaine pointed out that if he had not suffered a heart attack, needed triple bypass surgery, and, on the advice of his doctor, retired, he would have kept on driving. He was on the top of his game at that time and had he not left, especially following his magical year with Forrest Skipper in 1986, he thinks the Hall of Fame would have come knocking sooner, but he had no regrets.

“When everyone in your family is gone by the age of 50 and you live to be 83, you appreciate everything,” he said.

Fontaine grew up with 11 siblings and neither they nor his parents lived beyond the age of 50. Heart issues ran in Fontaine’s family and plagued him throughout the latter part of his life.

“When I retired, I got to travel with [my wife] Marsha and spend more time with [my son] Marc and that’s what mattered,” Fontaine said. “My career gave me a good life, but my family was my life.”

Those who knew Fontaine are aware of what a gifted storyteller he was and when asked if he had any particular stories in mind for Goshen, he said he hadn’t thought about it yet.

“I’m sure I could come up with something,” Fontaine said with a laugh. “My career was cut short, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have anything interesting to say.”

One of his favorite stories to tell was about the time he and his best friend, NHL Hall of Famer and New York Ranger Rod Gilbert, were walking down New York City’s 8th Ave. in midtown Manhattan and a fan came running up to them looking for an autograph.

“We were just walking up the street and this girl walks up to us and asks for an autograph,” Fontaine said. “So, Rod reaches for the pen and she says, ‘No, I want your autograph,’ and she hands the pen to me. That might have been the first time it happened but it wasn’t the last. How great was it to have two boys from Pointe-Aux-Trembles [QC] on the top [in their sports] at the same time? It was really something.”