Quiet and steady success wins the O’Brien race

Richard Moreau, a cousin and former babysitter of Yannick Gingras, has been voted Canada’s Trainer of the Year an unprecedented sixth straight year, but don’t expect the level-headed Quebecer to brag about it.

by Paul Delean

A cousin and former babysitter of top driver Yannick Gingras recently told Gingras he expected to be working for him someday, trimming his lawn in the Bahamas.

Richard Moreau was joking. He’s doing just fine in his own right.

Moreau, 54, this month was named Canada’s outstanding trainer for an unprecedented sixth consecutive year, after accumulating 315 wins and a career-high $4.6 million in earnings in 2018. At his regular pick-up hockey game, he was likened to six-time Super Bowl champ Tom Brady.

“It’s gratifying, and motivating, but I’m not somebody who looks for attention. I keep my two feet on the ground. The only publicity that matters for me is results,” Moreau said over lunch during a visit to Montreal to see his parents and son Gabriel, 21, a university student.

Although he’s based now in Ontario, Montreal is where Moreau got his start in harness racing almost four decades ago.

A neighbour, Robert Galardo, used to take him to the races at the now-defunct Blue Bonnets track, where Moreau got to watch driver/trainer Raymond Gingras (Yannick’s dad), married to his father’s sister Monique.

Horses hadn’t been part of Moreau’s daily life growing up. His father, Roland, worked in finance, and his mother, also named Monique, was a teacher. But there was something about the sport that captivated him from an early age.

“My uncle Raymond was my idol back then,” he said. “Now it’s Yannick.”

Through the Gingras family, Moreau landed a job at Blue Bonnets as a groom, working for several trainers.

He was also studying finance in college, and not liking it much.

“I’d go to school two days and the racetrack on the others. I was happier working outside than in. I quit school for the horses at 19, but I didn’t tell my parents for two weeks,” Moreau said. “They weren’t pleased. But things changed over time. Now, my mom is my biggest fan. She watches all the races. She’s congratulating me for wins before I’m even aware of them sometimes.”

Moreau said his progression in the sport was more steady than remarkable, with some good breaks along the way.

One of his dad’s co-workers at the bank helped him buy his first horses.

When driver/trainer Daniel Dube exited Quebec to take his shot in the U.S., he left behind half his stable, with Moreau as the recommended trainer.

When the Quebec racing industry fell on hard times at the turn of the century and Moreau shifted his base to Ontario, his contacts in his home province ensured a steady supply of new stock.

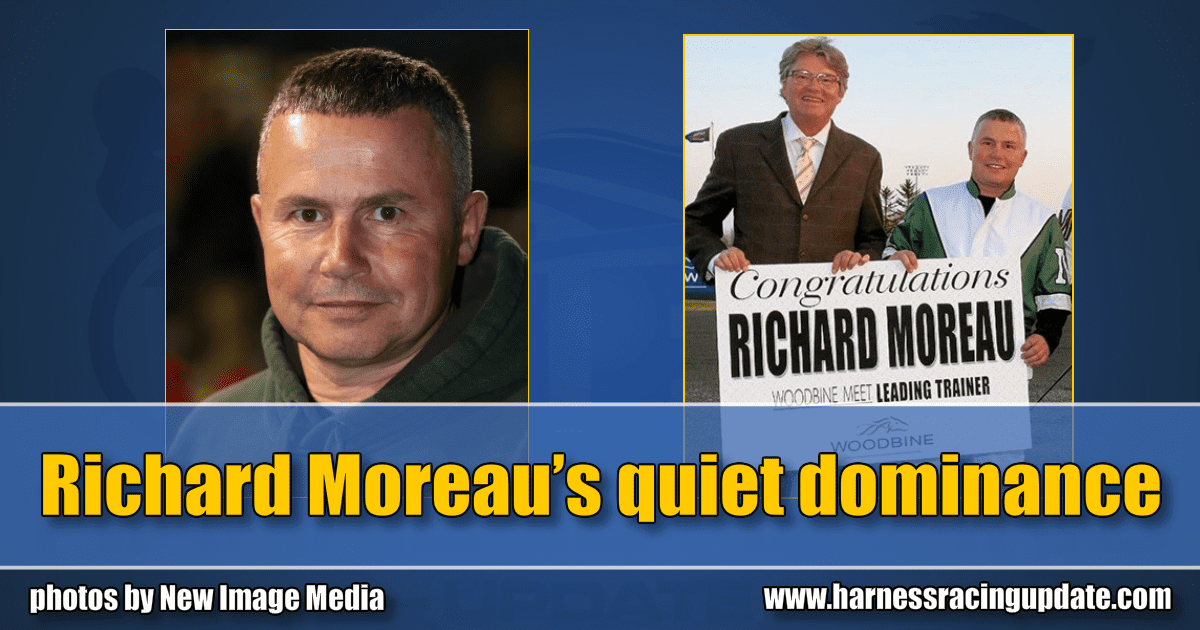

He quickly made a name for himself at Windsor Raceway before gradually upgrading his stable and expanding his reach to virtually all tracks in the province, including the biggest one, Woodbine Mohawk Park, where he was leading trainer in 2018.

After a long association with Sylvain Filion, “who I really respect,” Moreau now has Louis-Philippe Roy as his main driver, but the size and spread of his operation means he actually employs several.

“I try to get the best driver possible. That’s always been my way,” he said.

In a sport where fortunes often fluctuate wildly, Moreau has been a model of consistency. He’s topped 100 victories every year since 1996, winning with more than 20 per cent of his starters, to push his career total beyond 5,600. His stable has exceeded $1 million in earnings annually since 2000 for a total of more than $54 million and he’s done it the hard way, in the trenches.

Although he’s had a few major stakes winners along the way, including 2018 O’Brien Award recipient Jimmy Freight and 2013 Metro Pace victor Boomboom Ballykeel, Moreau’s stable consists primarily of overnight horses entered wherever they can be competitive. His three trailers are constantly on the road.

“I’m not a dreamer,” he said. “I didn’t have the bankroll starting out to breed or buy yearlings or the time and patience to wait to see if they’d be stakes horses. I preferred horses who were developed already. It worked and I stuck with it. I think I’ve proved myself, but I paid my dues. I persevered.”

His is a high-turnover operation, with an average of one horse moving in or out every day. “I respect the animals, but I don’t fall in love with them. We’ve usually got about 60 horses, but we’ve been up to 80. I always have room,” said Moreau. “Normally, we’ll have 11 to 14 racing on any given night. One Saturday, we had 24 in. At this point, I’m used to overseeing a large number of horses and so is my staff of 10. Everybody knows the routine. Everybody knows their job. I can do the entries now in about 20 minutes.”

He’s been asked about expanding into the U.S., but so far hasn’t been tempted. “I’ve got my hands full here and I’m happy. I’ve already travelled plenty in my life.”

While his profile in the industry has never been higher, Moreau’s vision of success has little to do with awards.

He’s proud of the fact respected trainers such as Marcel Barrieau and Dustin Jones entrusted horses to him this winter when they headed south. He’s proud of the 45-acre farm near Mohawk that he now owns outright. He’s also a newlywed, having tied the knot with his girlfriend of four years, Cheryl McGill, in November.

McGill, 32, a former show jumper and thoroughbred exercise rider who knew little about standardbreds, was working in security at the Mohawk paddock when Moreau invited the mother of two to lunch.

“It couldn’t be dinner because we both worked in the afternoon,” she said.

They hit it off immediately.

“He’s humble, he’s quiet, he’s level, he’s always the same person no matter what day it is or what’s going on,” she said.

“When I come home,” said Moreau, “that’s when I most have a sense of accomplishment.”